If you are interested in the economics of prescription drug importation to lower drug prices or follow related politics and policy, I recommend a new economic paper called Arbitrage Deterrence: A Theory of International Drug Pricing, published in a special edition of Health Management, Policy and Innovation, a journal published by the nation’s top business schools. The author, Stephen Salant, is professor emeritus of economics at the University of Michigan, formerly a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors and The RAND Corporation, where he was a founding co-editor of the RAND Journal of Economics. Salant’s paper supports personal drug importation and legalizing the importation of prescription drugs for commercial use so that wholesale pharmacies, including companies like Amazon and Costco, could tap into the parallel importation markets of other countries. The paper was funded by the Michigan Institute of Teaching and Research in Economics (MITRE).

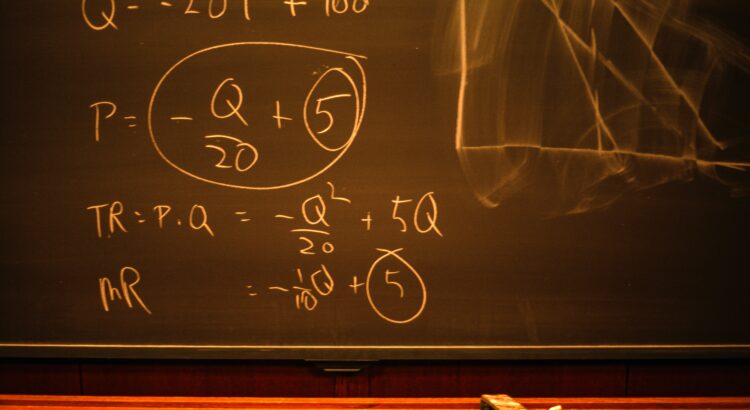

Salant’s math might be difficult to understand, but conceptually what the economic theory and modeling say is very straightforward: drug manufacturers have spent millions of dollars funding organizations to scare Americans away from safe personal drug importation because if they didn’t, many more people would avail themselves of lower drug prices in foreign countries. That’s why, according to Salant, drug companies “[blur] the distinction between dangerous counterfeit drugs and safe drugs sold by pharmacies licensed in other high-income countries.” This point is critical because it has gone ignored in the economic literature.

The theory covers four “stylized facts” of the international market in prescription drugs. First, drug prices in the U.S. are much higher than in other high-income countries. Second, governments in high-income foreign countries engage in some form of bargaining with drug companies on drug prices. Third, even foreign drug prices are much higher than the cost of production. Fourth, as discussed above, drug companies spend millions of dollars each year scaring Americans away from buying safe and more affordable prescription drugs. Other economic theorists have addressed pieces of this importation and drug price puzzle, but none until now has addressed all of them.

Citing JAMA, Salant states, “a mere 1.5% of U.S. adults purchasing prescription medications bought them abroad to save money” as proof that pharma’s campaigns “to scare and confuse potential importers [have] succeeded.” The theory holds that in the absence of scare tactics, far more individual patients would import cheaper medicines safely. Why? Because it’s not economically rational for patients not to import lower-cost and safe prescription drugs.

Salant also asserts that federal law does not deter individuals from importing prescription drugs, because patients are not prosecuted for the “crime.” What he does not say is something that places the FDA’s non-enforcement policy clearly within the law: Congress has declared in Section 804 of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act that the Secretary of Health and Human Services should permit the otherwise prohibited importation of prescription drugs for personal use that is not an unreasonable risk to the patient’s health. 21 U.S.C. § 384(j)(1). There is no Congressional declaration encouraging the non-compliant importation of prescription drugs for commercial use.

This de facto decriminalization of personal drug importation means that the U.S. drug market is connected to foreign markets with lower drug prices. Before this paper, the economics literature limited their categories for analysis to (1) systems of legal drug importation, where prices are affected by open parallel trade in pharmaceuticals, such as in the European Union, or (2) systems where drug importation is entirely illegal, and thus prices in one country are not affected by those in another. Salant introduces what he calls “a neglected intermediate case where importing prescription drugs is illegal, but nonetheless the markets are connected.”

In other words, drug prices in foreign countries affect U.S. drug prices, and vice versa. Since some drug importation legislation calls for wholesale importation, in addition to personal importation, Salant analyzes both with similar results. In the absence of scare tactics on personal drug importation or legislative reforms to facilitate safe commercial importation from high-income countries, the threat of arbitrage would lead drug companies to lower prices in the U.S. but negotiate higher prices in foreign markets.

Consider how this international drug price dynamic may affect the politics of the issue. In the summer of 2022, a policy debate in the Senate HELP committee ensued with Sens. Bernie Sanders and Rand Paul agreeing that the time had come to expand importation. Salant’s paper speaks directly to comments about importation by Sens. Mitt Romney and Kaine. Quoting from Kaiser Health News:

“A robust discussion between Republican and Democratic senators ensued. Among the most notable moments: Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) asked whether importing drugs from countries with price controls would translate into a form of price control in the U.S. Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) said his father breaks the law by getting his glaucoma medication from Canada.”

To Sen. Romney and others who view importation as importing drug price controls, Salant’s paper shows that legalizing commercial importation is a legitimate free market response to government-negotiated lower drug prices in other high-income countries. Sen. Kaine’s father’s personal drug imports exemplify the behavior of Americans who have done the research necessary to import a prescription drug safely from a Canadian pharmacy, which is the importation that Congress declared should be permitted.

The paper makes allowances only for imports from high-income countries. Many people in the U.S., and worldwide, import medications from non-high-income countries, particularly India. Of course, India is the largest supplier of FDA-approved generic drugs sold in U.S. pharmacies and personal imports from India can be safe as well. However, it makes sense that regulatory reforms to expressly permit personal imports or legalize commercial imports would be based on trade between the U.S., the EU, and other high-income countries with the most stringent pharmaceutical and pharmacy standards.